What a beautiful day! I have been patiently waiting for a long time before I could come up with this post for all of you. I have been studying Linguistics and Sociolinguistics for about 10 years now and nothing, I mean nothing has made me feel so happy in my academic life like that day one of my professors said that “maybe, Rodrigo, you don’t understand quite well the black American rappers because you are not studying the English they speak.” That definitely blew my mind and I did not know what to do and when I was about to ask him the question, he interrupted me and said “you should work on your African American Vernacular English(AAVE) which is best known as Black English or Ebonics” . That is when it all took off!

The emergence of AAVE

When studying the historical growth and development of the English language it is apparent that language changes over time and that change, although not always accepted, is nonetheless inevitable. In order to understand the English language it is also essential to understand the nature of the language’s variations to the fullest extent. This importance is due to the scope of changes that the English language has undergone throughout history.From Old English to the late modern English time periods, the language has taken on different variations in different parts of the world. There are many assumptions as to the emergence of AAVE, but one of the most reasonable explanations is the speculation by Algeo and Pyles, that perhaps the variant did not begin in the early years of slavery. It is possible that most slave ships consisted of homogeneous groups who spoke the same language. It may not be until the slaves were actually placed on a heterogeneous plantation with no predominant language, that the idea of desperately needing to communicate with others caused the slaves to begin speaking in pidgin languages.

Dillard asserts that many people feel insulted when told that their ancestors had to rely on a pidgin language which is essentially the convergence of two separate and different dialects into one. Pidgins perhaps are misunderstood by those people because they, like other languages, have regular principles of sentence construction. Pidgins, when understood, should be viewed as historically influential because many languages emerged from the use of this system.

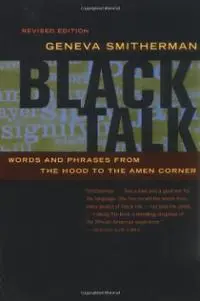

Pidgins, as they develop, are historical processes and they provide an adequate basis for the explanation of the emergence of AAVE. According to Smitherman, “Black talk crosses boundaries of age, gender, religion, region, and social class because it all comes from the same source: the African American Experience and the oral tradition embedded in that experience.”

Excerpt from African American Vernacular English: A linguistic study on the dialect and the social implications for its speakers by Angela D. Holmer and Professor Bob Broad

Watch Broken English and see for yourself how some professors explain the emergence of AAVE:

Isn’t it interesting? Think about yourself, who are not a native speaker, learning a second language. Let me put it this way, if you are from Brazil, your mother tongue is Brazilian Portuguese, and I take you to China. When you get there I institute the first rule: you cannot use your own language to communicate, you will have to use Mandarin or Cantonese. What would happen to you? Certainly, you would have to remain silent for a while because you do not know that language yet. However, as time goes by, eventually, you will start learning a word here and there and you will try to put them together in order to communicate your thoughts and needs. Obviously, your Mandarin would be broken and never like that language spoken by the native speakers, but you would start understanding and making yourself understood. Do I make sense?

This is exactly what happened to blacks who were brought into the U.S as slaves. They had to develop another language based on their mother tongue and the new language imposed to them: English. Throughout the years, their children were born in an English speaking country, however their parents spoke that other language they had created. Would they be considered bilingual children? Maybe! Some linguists claim they are, some others call that “slang”, some consider it to be “wrong” and some others would rather see it as a dialect of the English language. Which side do you take?

Well, watch this amazing and articulate video by Jamila Lyiscott who is currently an advanced doctoral candidate and adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College where her work focuses on the education of the African Diaspora. She is also an adjunct professor at Long Island University where she teaches on adult and adolescent literacy within the Urban Education system.

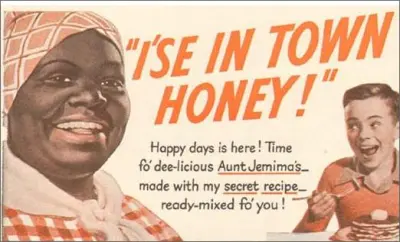

Labels and myths

There are many myths concerning AAVE but one myth that is in dire need of being dismissed is that variant English is inferior to Standard English. This myth may be due to the tendency for our society to automatically label that the more prestigious one is the more “correct” and the lower the class the more incorrect their dialect becomes.D. Byren argues: Correct can only mean “socially acceptable” and apart from this, has no meaning as applied to language. The social acceptability and hence “correctness” of any form or word is determined, not by reason or logic or merit, but solely by the hearer’s emotional attitude toward it.

Byren speaks from a linguistic point of view when he attempts to diminish the labels right and wrong as far as speakers of the language are concerned. One very influential person in the study of variant English is sociolinguist, William Labov.

William Labov‘s ideas center around the fact that the idea of a standard language, as it is one “correct” form of the language has caused us to apply negative stereotypes to the speakers of the variant English. It is important to understand that variant English has a system just as “standard” English, and that the systems of this variant are just as consistent as those within the standard.

Excerpt from African American Vernacular English: A linguistic study on the dialect and the social implications for its speakers by Angela D. Holmer and Professor Bob Broad

But where do I find Black English today?

Is modern Black English the same spoken back in the dates? Well, the basis remain but Black English has been influenced by other languages, culture, music etc. Today, you can find Black English everywhere: TV shows, movies, Hip-Hop, Rap, Poetry. Some jokes are told and they only make sense in black English. Can you figure out these ones below? Are they racist? Stereotypical names are used such as Sheniqua, Tyrone, Antwan (Try to put these names on google and see the images – Did you find any white person?) So as you can see, there are African-American names too.

Due to the concept that this dialect is just wrong, some African Americans who are not versed in “Standard” or “Mainstream” English get knocked out of a job opportunity for linguistic reasons. Watch this documentary and see for yourself how things are seen by them.

However, if you are losing opportunities in the market, what should you do? Fight for equality regarding language or code-switching?

Garrard McClendon, author of “Ax or Ask: The African American Guide to Better English” has been interviewed. This is the point he is trying to get across with:

As you can see there are lots to be discussed and learned and I do not get tired of reading or attending classes and watching videos about Black English. Well, I think you have enough material here to start your studies on African American Vernacular English . In 2010, these people, including Garrard McClendon came together for a conversation and, as you can see, blacks think differently when it comes to Ebonics. See it for yourself:

I really do hope you all could get acquainted with my favorite dialect of the English language. Hope this post could confuse you in terms of “correct” and “incorrect” or “adequate” and “inadequate”.

If you came this far and are reading this last sentence, let me know by commenting this post and sharing more videos, music and/or TV shows.

Still don’t quite know what AAVE is all about? I highly recommend this animation below.

This material has been selected, analyzed, adapted, and put together by Rodrigo P. Honorato.

Hey bro, lemme ask you somethin’ here… I was reading an article about “Ebonics” you wrote on your website (for the record, this website is fucking amazing! nice work man) and are there any book about ebonics for downloading, by any chance?

LikeLike

Great shit! It’s a shame that AAVE is seen as an inferior variety of English, but it’s not better or worse, just different. Just like my Australian accent is different to that of an American, but not better or worse. But I think there’s little doubt that black American English has a negative perception and many black Americans recognise that because they readily switch to standard English (or something approaching it) when they feel they want to be taken seriously. And those that don’t have that ability suffer in terms of employment prospects.

I think the issue could be that it’s not just a different accent, but that it violates quite a few ‘standard’ grammatical rules, making it seem less educated. If it were just a difference in accent (such as Texas v California v Mid-west), it might be a different issue. But then again, the accent itself is an unmistakably “Black” accent, which probably in itself causes issues for its speakers. I think we see this in the fact that people like Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey and Will Smith speak in what appears (to me, anyway) to be a standard American accent when they speak publicly, suggesting that even a “Black” accent is socially damaging. This is very complex but also very interesting and I can see why you love to study it.

LikeLike

I totally agree with you, Ralph. I love the varieties, but unfortunately Black English has been stigmatized for a historical reason as well as social issues. Here in Brazil, when I use my black English, people look at it as a positive trace like “wow, you talk like those rappers or those guys from GTA San Andreas or those guys from the movies…” but when I was working in the U.S., I would use standard American English.

I’ve heard from Americans that I sounded educated and it was nice since I wasn’t even from there.

LikeLike